Richard Fontaine

President Donald Trump swept back into power promising a new American approach to the world. As he was in 2017, Trump has been harshly critical of his predecessor’s foreign policy and pledged major differences in priorities and style. His supporters cheer the return to an “America first” attitude, one that emphasises toughness, seeks concrete benefits from any foreign engagements, and centres on hard-headed deal making. His detractors fear a cramped, short-term world-view combined with an erratic, transactional approach to a complicated international environment. Either way, much of the world now braces for significant policy departures and prepares for a major lurch in US foreign policy.

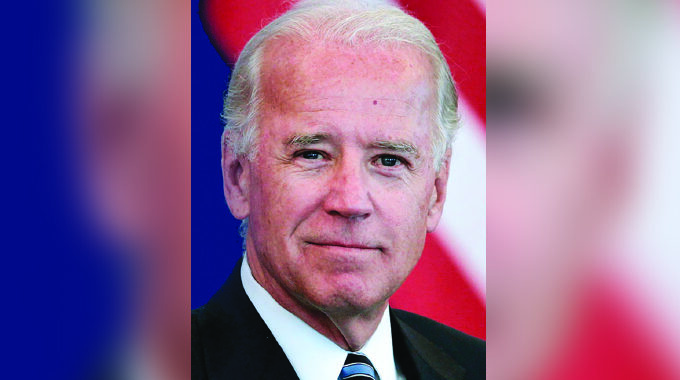

To be sure, a second Trump era promises significant changes after four years of President Joe Biden’s administration. Biden firmly committed to supporting Ukraine, defending Taiwan militarily, fulfilling the United States’ climate change commitments, and centring democracy in US foreign policy. He stressed the benefits of the United States’ alliances and the threats that China and other revisionist powers pose to the global order. Trump, on the other hand, questions the need to continue aiding Ukraine, declines to commit to Taiwan’s protection, downplays climate change, and deprioritises the promotion of democracy and human rights. He often portrays US allies as free riders enriching themselves under US protection and emphasises the unfairness of trade deficits with countries such as China more than any systemic risks these countries might pose. The new president will surely spend his first weeks in office issuing executive orders and other directives aimed at visibly reversing Biden’s policies.

For all the differences, however, there will likely be far more continuity between the two administrations than meets the eye. Across administrations — even ones as different as those of Biden and Trump — foreign policy is something like an iceberg. The visible portion is gleaming and jagged and draws much of the attention. Yet it also has a far bigger and under examined foundation, one that tends to remain mostly unchanged. Even as they focus on Trump’s differences in style and substance, observers should not ignore the potential stability in the United States’ approach to the world. Otherwise, they may misunderstand policy, attributing it to a specific president, rather than more firmly rooted in bipartisan consensus and likely to endure.

PICKING UP WHERE WE LEFT OFF

In 2021, Biden pledged to be everything that Trump was not. Biden re-entered the Paris climate accord after his predecessor’s withdrawal, emphasised NATO’s importance after Trump was critical, and assured allies that “America is back.” Whereas Trump made his first overseas trip as president to Saudi Arabia, Biden pledged to make the regime in Riyadh a pariah. The president stopped Trump’s withdrawal from the World Health Organisation, quickly patched up burden-sharing disputes with Asian allies, and began planning Summit for Democracy gatherings, the first of which he hosted in December 2021.

On many other issues, however, Biden retained the essence of Trump’s approach. Key documents issued during Trump’s first term characterised China and Russia as strategic competitors of the United States, a framing Biden embraced. Biden kept the Trump-era tariffs on China and expanded controls on technology transfers that began under Trump. He executed the Afghanistan withdrawal agreement negotiated between Trump’s team and the Taliban, remained outside the Iran nuclear deal, and, like Trump — but unlike President Barack Obama — provided lethal aid to the government in Ukraine. Biden sought to extend the Abraham Accords, a key Trump-era foreign policy success in the Middle East, and over time, he attempted to make Saudi Arabia a US treaty ally.

The two administrations could hardly have been more different in style and rhetoric. In the underlying substance of their policies, however, there was more continuity than the casual observer might have appreciated.

Many such areas of constancy will almost certainly remain in the next Trump presidency. The incoming administration’s approach to Israel, for instance, will likely be broadly similar, combining military support with protection both from Iranian missiles and diplomatic attacks at the United Nations and elsewhere. Policy toward Saudi Arabia will be comparable now that Biden has embraced the government in Riyadh and seeks regional normalization. Under Trump, Washington is poised to continue to see China as its foremost global challenger and endeavour to build domestic sources of strength. Even as the new administration rails against US allies on issues such as defence spending and trade, it is likely to seek tighter partnerships abroad, particularly in the Indo-Pacific, to better compete with Beijing. The Quad (Quadrilateral Security Dialogue) among Australia, India, Japan, and the United States — which was established in 2007, revived by Trump, and upgraded by Biden — will endure, just as the AUKUS defence technology sharing pact among Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States is likely to do.

Trump will probably back the bipartisan effort to deepen ties with India, an effort Biden supported but that predated him by several administrations. Biden and Trump also share a fondness for an economic protectionism that combines tariffs, “Buy America” provisions, import substitution, reshoring domestic manufacturing, and scepticism of multilateral trade agreements.

Stylistic differences between the two will remain obvious, but even here there will be exceptions. Trump is often seen as the unilateralist, offering too little consideration to the concerns of the United States’ closest allies. Yet Biden unilaterally withdrew US forces from Afghanistan over the warnings of some of those very allies. Trump issues foreign policy diktats by social media, abjuring international consultation and consensus, but the Biden administration itself announced export controls on technology to China without the agreement of US partners. Both presidents emphasise the power of personal relationships with world leaders and their own prowess in navigating them, albeit in very different ways.

THE MORE THINGS CHANGE

Foreign policy stability across US administrations is nothing new. Even in controversial areas and frequently in spite of campaign promises to the contrary, presidents often retain a good deal of their predecessor’s foreign policy. During his first presidential campaign, Obama railed against the excesses of President George W Bush’s “war on terror,” and then, as president, he went on to bomb more countries than Bush did. As a first-term candidate, Trump denounced NAFTA and the US-Korea Free Trade Agreement but then signed on to new versions with mostly cosmetic changes. For all of his carping about NATO’s free-riding obsolescence, Trump oversaw the alliance’s expansion, backing the addition of Montenegro during his first year in office.

Administrations of very different stripes can nevertheless share similarities because fundamental American realities change slowly.

The deep wellsprings of US foreign policy—the geographic, economic, and political conditions that shape Washington’s approach—are relatively stable. Policymakers tend to identify national interests and values in similar ways, even if their methods for attaining them vary significantly.

For many decades, for example, Washington has tried to prevent Eurasia from being dominated by a hostile power. It has insisted on maritime freedom, critical for a country that trades significantly by sea.

The United States’ interest in stable supplies of Middle Eastern energy, along with concerns about terrorism and long-standing support for Israel, gives Washington an interest in ensuring geopolitical stability in that region. It seeks open international markets for its goods, stations its military forces abroad, urges allies to strengthen their defences, and seeks to deny nuclear weapons to adversarial countries, such as Iran and North Korea.

Examples of long-standing policy continuity are legion. The United States has, for instance, pursued political change in Cuba since the days of President Dwight Eisenhower. It has harangued NATO members to spend more on defence since President John F Kennedy. Washington has retained diplomatic ties to China since President Richard Nixon, prepared to use military force to defend interests in the Middle East since President Jimmy Carter, and pursued missile defence since President Ronald Reagan. Each administration since President Bill Clinton’s has negotiated (usually unsuccessfully) with North Korea and each one has pursued an Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement.

The US Congress plays a role in ensuring a measure of stability. As Washington switched diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing, for example, Congress passed the Taiwan Relations Act, which requires US support for the island. It has kept the Cuban embargo in force regardless of different presidents’ skepticism. When Carter tried to withdraw US forces from South Korea in 1977, Congress intervened, and it did so again when Trump made similar noises, prohibiting the removal of troops below a specified level. When Trump expressed warmth toward Russia early in his first term, Congress moved to enshrine into law four Obama-era executive orders that sanctioned Moscow. It has also passed legislation requiring congressional approval for a U.S. withdrawal from NATO.

NEW BOSS, OLD RULES

Even if an administration’s policy substance—as expressed in laws, strategy documents, international agreements, and the disposition of military forces—remains the same, it still, of course, has significant power to shake things up. To undermine NATO deterrence, the commander in chief does not need to withdraw from the pact; he can simply suggest that the United States will not defend an ally under attack. If a president is unhappy with Japan, he might threaten to withdraw US troops if Tokyo does not cough up more funding for host nation support. The 2020 US-Mexico-Canada Agreement eliminates tariffs, but during the transition period, Trump said he might levy 25 percent tariffs on the other two members anyway.

For all that, foreign policy’s underlying tendency toward continuity could lead the Trump administration in surprising directions. A weakened, frightened Iran may well try to negotiate with the new team, and Trump, like Obama, might pursue a deal to cap Tehran’s uranium enrichment. Rather than seeking to end North Korea’s nuclear program through high-level summitry or the threat of force, as he did in his first term, Trump may well rely on deterrence and containment—just as other presidents have. The new administration might pick up where Biden left off on Israeli-Saudi normalization efforts and could continue some support to Ukraine. Trump will likely seek, like Obama and Biden, to prioritise the Indo-Pacific in US foreign policy and will face challenges, as did they, in doing so. He will also probably try to avoid direct military conflict with other countries, as Biden has done with Russia, in Afghanistan, and in the Middle East.

Trump will usher in departures, sometimes dramatic ones, in American foreign policy. But those changes will compose just a fraction of the total. The stability of U.S. interests and values, the role of Congress, and the realities of today’s world will demand a significant measure of constancy. Although it is bent on reversing Biden’s approach, the incoming team may itself be surprised to find out how much the two administrations share. – foreignaffairs.com <http://foreignaffairs.com/>

· Richard Fontaine is CEO of the Center for a New American Security. He has worked at the US Department of State, on the National Security Council, and as a foreign policy adviser to US Senator John McCain